A student in the College of Engineering, Linn had planned on returning to VCU after his tour of duty but unfortunately never made it back. He was killed during an ambush.

By Joan Tupponce

Credit: VCU News

On Jan. 26, 2005, Dick Linn left his home heading to a sales call. About 40 miles into the trip, the phone rang. It was his mother, telling him that the Marines were trying to reach him.

“When I called them back, they said, ‘We need to talk to you,’” Linn recalled.

He tried to deny the fears that overtook him, but he couldn’t stop his body from physically shaking. He tried his best to hold onto hope.

“You think he’s going to be OK,” he said of his older son, Lance Cpl. Karl Linn, who had been deployed to Iraq. “He’s out in the desert. He should be OK.”

Linn returned home. About five minutes later, two Marines in dress blues knocked on the door. Karl had been killed in an ambush.

“Once they told me, I was the only one in the family that knew it at that time,” Linn said.

The worst was yet to come — he had to tell his family. He first told his younger son, Tan. But telling his wife, Malisa, would be even harder.

“It’s the worst thing I ever did in my life. I went over to where she was taking care of some kids. I sat her down on the couch and said, ‘Karl, he didn’t make it. He’s dead.’

“It about killed me to do that,” Linn said. “I thought she was going to have a stroke. She screamed three or four times and threw herself on the floor. From then on it was a blur.”

The deadliest day in Iraq

At the time, Jan. 26, 2005, was the deadliest day in Iraq. Thirty-seven soldiers lost their lives — four, including Karl, were Marines, members of 4th Combat Engineer Battalion, Charlie Company. The significance of the day and the attack on those four young men caught the attention of CNN correspondent Tom Foreman and producer Amanda Townsend Turnbull.

“Tom and I wanted to humanize what was happening and to show these moments. We wanted to tell a story about how these incidents had such a meaningful impact on the families they left behind and the soldiers that were serving on that mission,” Turnbull said.

Everything about the story spoke to the complexity of the war and the young people who were prepared to do “what my nation asks of me even in these complicated circumstances,” Foreman said.

Foreman and Turnbull spoke with Karl Linn’s parents and members of the families of the three other young men who were killed in the ambush at the River of Secrets, as well as some of the Marines who were on the mission.

Turnbull has worn different hats in her career and worked on thousands of stories. This one made a lasting impact on her, she said. “I still have my notebook from this. It still stays with me.”

One thing that struck Foreman the most about Karl after interviewing his family was how “he was the center of the family.”

“With everyone else we talked to, I was aware of the expanding family around them,” Foreman said. “With Karl, it was contained within their small family, and in that sense, it was so difficult. It seemed that he had so much promise and that meant so much to that family.”

It was incredibly touching for Foreman, just being in the space where these four young men had lived and laughed.

“I became aware of the emptiness they left,” he said. “Even today, if we go anywhere near where we interviewed the families, it comes back to me. You pull up to a house and before you pull up, it’s just a house, and then you become aware of everything that passed in the house.”

Happier times in the Linn household

The Linn household in Chesterfield County was buzzing with activity years ago when Karl and his brother Tan were young. Karl was always quiet, mild mannered and inquisitive.

“He was a quick learner,” his dad said. “He was reading before he was 5. He was always curious to find out how things work.”

Karl had an interest in science, spaceships and airplanes.

“He was like an encyclopedia,” Linn said of Karl’s ability to retain facts. “He was wise, like an old man.”

“He was a nerd,” Malisa said.

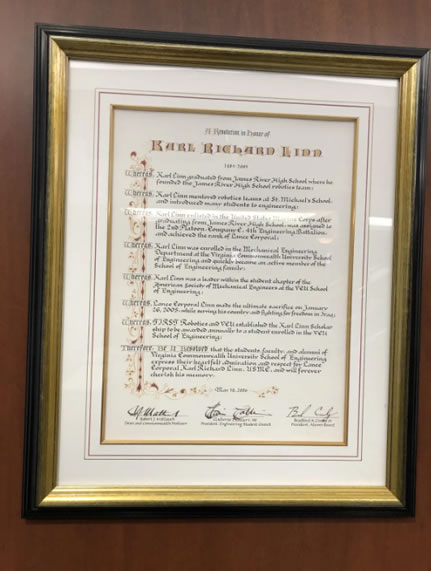

Karl developed an interest in robotics and co-founded a First Robotics team at James River High School in Chesterfield. He also had a talent for art.

“He was always sketching things,” his father said. “He helped paint a mural on the wall in his classroom during his senior year in high school.”

Like many others, the events of 9/11 impacted Karl when he was in high school, so much so that he wanted to join the Marines. Not yet 18, Karl wanted to enlist early but his father told him to “give it some thought.”

Karl instead joined the Marines as a reservist in the delayed entry program in June 2002. That fall he received an Alcoa Community Scholarship to attend Virginia Commonwealth University to study mechanical engineering.

“I’m sure his participation in First Robotics had a lot to do with it,” Dick Linn said of the scholarship, adding that when Karl started at VCU in 2002 he lived on campus. “He really enjoyed the engineering program there.”

Karl completed Marine boot camp at Parris Island in South Carolina in the summer of 2003 and later trained in his military occupational specialties and combat in the summer of 2004 after his second year at VCU.

Only 5 feet, 6 inches tall, Karl was “a little Marine,” Linn said. “He was top grad in his combat engineer class.” He was only 20 when he was deployed to Iraq after finishing his sophomore year. He planned to return to VCU.

An asset to his unit

Karl had learned about Russian weapons earlier in his life and quickly became an expert on them.

“He could take them apart and put them back together,” his father said.

That knowledge made him a valued asset in his unit.

As a member of the 4th Combat Engineer Battalion, Charlie Company, he was first sent to a post in the northernmost part of Iraq.

“It was the middle of nowhere,” Linn said. He said that fact made him feel more comfortable about Karl being deployed.

Master Gunnery Sgt. Harry “Butch” Dreany, who now works at the Office of Naval Research as an artificial intelligence capabilities analyst, was the platoon sergeant and a staff sergeant in Karl’s unit. Dreany remembers his first impression of Karl was that the young Marine was introverted but had a superior level of intelligence.

“He would become one of our go-to guys to get the job done,” Dreany said. “He had a quiet intelligence.”

Karl was a replacement in the unit, but it only took him a few weeks to quickly become one of the guys, Dreany said.

“As a combat engineer, we had to locate or dispose of numerous weapons caches. The enemy had a lot of different ones, especially Russian. Karl was already versed in Russian weapons and that became pretty useful,” he said. “A weapons cache can tell you a story about the enemy, like what condition the weapons are in and how much ammo they have. From that, we could tell if the group was organized or disorganized.

Karl’s unit was a combat arms unit with the expectation of being in combat.

“We were working with explosives, mines and improvised explosive devices,” Dreany said.

The ambush

On the mission the night of Jan. 26, Karl filled in for another Marine who wasn’t feeling well.

“Everyone is trained the same,” Dreany said. “This was a big operation.”

The unit was expecting a lot of insurgents — 10 to 15 — in a house next to a mosque. They expected enemy engagement.

“They got to the house and it was empty. There was no furniture in there. It looked like nothing was going on. We had the feeling that we had been duped by the informant who provided intelligence,” Dreany said. “On the way out of the city, we were ambushed. We knew we had been set up.”

A reporter and photographer from WABC television station in New York were embedded with the unit and caught on tape the streaked flashes of gunfire and rocket-propelled grenades that lit up the pitch-black skies during the ambush.

The row of Humvees sped up to outrun the attack. Karl and three fellow Marines were in the open back on the passenger side of one of the last Humvees in the line.

The Marines were traveling on a straight road and the enemy was elevated, taking positions on the tops of buildings. In that type of situation, “you are in the kill zone of the ambush,” Dreany said.

Everyone on the open-backed Humvee carrying Karl and seven other Marines thought they had cleared the gunfire when a rocket-propelled grenade was fired from the mosque. It was the end zone of its reach, about 1,000 yards, when it struck the back of the vehicle.

Two of the Marines were dead at the scene. Karl and another, Jonathan Bowling from Southwest Virginia, were alive and helicoptered out but succumbed to their injuries on the ride. The other four Marines in the back were injured but survived the ambush.

“You look back and think, if this hadn’t happened what the result would have been. I thought about it in the years since him,” Foreman of CNN, said of Karl. “I think back to the four young men we covered.”

Following in Karl Linn’s footsteps

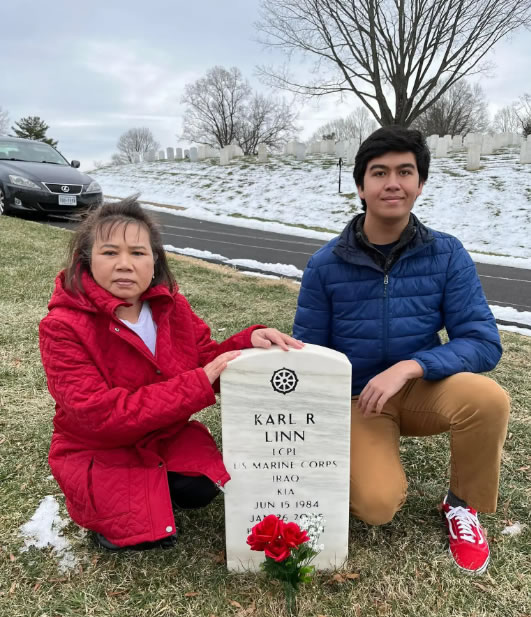

Fourteen years after Karl Linn was killed in Iraq, a VCU junior named Roman Cutler — who is majoring in mechanical engineering like Karl — was awarded a First Robotics scholarship, in honor of Karl, from the College of Engineering.

In the past year, Cutler has had the chance to meet the Linn family and learn about Karl. Cutler found that he and Karl shared the love of robotics and taking things apart to figure out what made them run. He also discovered that Karl’s mother was from Thailand, like his mother.

“I was intrigued to learn more about Karl and his legacy,” Cutler said. “The [tribute] in the Engineering West Hall at VCU about Karl only tells part of the story. Being able to close the gap gave me a picture of him in my mind. To me, you feel more connected to someone when you learn the personal aspect.”

Being in the home and meeting the family showed “me that there was something special there,” Cutler said.

“Finding out how he lived his life made me want to recognize him and show support. It also made me feel at home. Mr. Linn said I am part of their family now,” Cutler said.

Saluting a life well-lived

Karl was given a full military funeral at Culpeper National Cemetery, a cemetery for members of the armed forces. He is buried next to his grandfather, Robert C. Linn.

“There was quite a line of cars in the funeral procession,” Dick Linn said. “When we drove through Goochland, people were lining the streets to watch the procession. State troopers that were stationed at major intersections saluted.”

Senator Mark Warner, who was governor of Virginia at the time of Karl’s death, remembers Karl’s story.

Dreany still feels a close connection to Karl and all of the other members of the unit.

“It’s those moments that you are as close with anybody as you have been with in your life. I would trust them with my life,” Dreany said of his fellow Marines, remembering Karl and the other three killed that day. “As a Marine, we promise to never forget.”