Connecting Kids, Schools, Family, and Community

By Joan Tupponce

Mondays at Greenwood Elementary School in Glen Allen are special celebrations for children and staff. Every Monday morning, the moment students step off the bus or get out of a carpool vehicle, they are greeted with lively music and entertainment – everything from a drum line or a pep band to a dance or step team. The merriment continues as they enter into the school.

Students also get high fives, not only from Principal Ryan Stein, but from all of the teachers at Greenwood. “You can feel the love from the teachers,” Stein says. “They are in the hallway hugging all the kids. We want to make sure we connect with every child, and they feel seen and heard before that ‘sixty-sixth hour’ hits.”

These types of experiences stem from Stein’s philosophy on learning. He calls it Lifeline 65. Sixty-five represents the total number of hours kids are away from school over the weekend, Friday through Monday. In this philosophy, the sixty-sixth hour – the first hour students are back in the school environment – becomes very important. “We want to build a foundation of fun and love,” Stein says. “We want to make sure we reach every child on Friday and Monday. School can be a scary place or a place that is not so pleasant. That’s why I told our teachers, I want us to be known for Mondays.”

Small connections, he adds, “can lead to extraordinary achievements. Our teachers are the ones who make it happen at our school.”

Keeping the Faith

Stein’s enthusiasm for education and his optimism were cultivated when he was young. Growing up was a “challenging time, but both of my parents loved me and my brother very much,” he says, referring to his parents’ divorce when he was in fourth grade. “My mom did a lot of nonprofit work, and we were part of a lot of the things she was doing.” His father was “the most outgoing human I have ever been around. I’m lucky to have a little of both in me,” he says of his parents.

Stein’s school life deteriorated because of the tense situation at home leading up to his parents’ divorce. His grades fell, and he withdrew socially. None of his teachers or administrators at school noticed what he was going through until fifth grade. That’s when he met Mr. Decrosta. It was this teacher’s kindness and the time he spent with the 10-year-old boy that led to Stein regaining his inner faith and self-confidence.

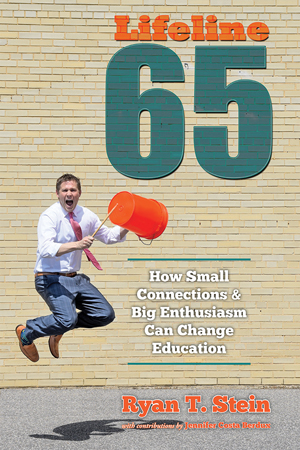

That experience inspired Stein’s philosophy and his new book, Lifeline 65: How Small Connections and Big Enthusiasm Can Change Education.

“Some of the children I have worked with as a teacher and principal might not have had the experience I had as a child, and I keep that in mind,” he says of the privilege of having two parents who loved him. “I’m purposeful with what we say and do at school. I share my personal experience to make relationships and connect with kids.”

After graduating from Randolph-Macon College, Stein’s first teaching assignment was at Echo Lake Elementary School in Henrico County. After five years, he moved to Pinchbeck Elementary School, where in 2011, he won Virginia’s Super Teacher Award. The following year, he was featured on the Rachael Ray Show as a top-five national educator.

On the show, the teachers were treated to a new wardrobe and a makeover, Stein says. He played on that idea after he was named principal of Greenwood Elementary when the school began treating ten kids to a shopping spree at J.C. Penney during spring break. “I wanted to give back because of my experience with Rachael Ray.”

At Greenwood, teachers nominated students for the shopping spree and then, ten names were pulled from a hat. To qualify, students had to live what Stein called the school’s Gator Values and be recognized as student of the month.

Stein knew when he moved into an administrative position at Greenwood – he’s starting his fourth year at the school – he would work to implement his philosophy of building relationships, which would ultimately become the subject of his Lifeline 65 book.

“To me, you can’t teach a child to read or multiply if they don’t want to come to school,” he says. “Before I came to Greenwood, they had issues with attendance and student discipline. In three years, we have knocked that out. They [the students] are now scoring with some of the highest schools in Henrico.”

Finding Inspiration

In 2017, Stein had the opportunity to visit the Ron Clark Academy, a highly acclaimed nonprofit middle school in southeast Atlanta that has received national and international success for its educational methods. During his visit, he was able to see the school’s House System in action and wondered how he might incorporate a similar system at a public elementary school.

He surveyed staff and students at Greenwood the following January and discovered students wanted more opportunities for leadership, as well as the chance to mentor younger kids. Students also said they were lacking friends in other classes or grade levels. Teachers wanted a common incentive that could be given out every day.

Stein shared the results at a faculty meeting in the spring of 2018. “My sales pitch was, ‘What if we could accomplish all these things by

doing this really cool house system?’ and I broke down the vision of what it could look like,” he says.

Using the Ron Clark model, the school would be split into five houses, each named after one of the school’s core values. Each house would be represented by a different color. Students would compete every day to earn a point for living the school’s values. Each house would also have a fable tied into its core value.

At the faculty meeting, Stein says he was enthusiastic about the house system. “I kept going through all these things I would love to do, such as monthly breakfasts with the whole house and the parents, and providing the opportunity for older kids to mentor younger kids,” Stein says. “They were eating it up, and everyone’s hand went up, and they asked the same thing: How are we going to afford this?”

Stein personally reached out to different companies he thought would be interested in supporting the school. He explained that five businesses – Joyner Fine Properties, Fulton Bank, Wegmans, Richmond Strikers, and McKesson Medical-Surgical – believed in this mission and would donate $3,000 each if the school flipped the switch on the program.

Five Houses, One Family

Stein and the team of teachers at Greenwood created five houses for last year’s Greenwood Gators, and assigned a name and a value with a corresponding color to each house.

For example, the house of Sol was marked by its optimism; its color was yellow. One house was gratitude and its color was green. Another house was accountability and its color was purple.

Because it was the program’s first year, teachers were able to choose what value spoke to them. “I chose Sol because I’m so optimistic,” says Stein.

Next came the important part. Teachers and administrators sat down and talked about each child individually and put them into houses. They considered what value spoke to each student before making final decisions.

Parents and students were informed about their designated house via a postcard sent in the mail. For the annual open house last August, a Bruno Mars and Motown cover band performed. That evening, students received shirts and wristbands for their respective house.

“Normally, for an open house we have 80 percent attendance,” Stein says. “Last year, over 95 percent came, which is unheard of for our school. Everyone was so excited.”

Last year, new students enrolling after the first day of school were able to spin a wheel in front of the whole school at a pep rally. Whatever house the wheel landed on was their house. “The parents came in and filmed it,” Stein says. “All the kids jumped on the new kids and welcomed them.”

This year, incoming kindergarteners will learn their designated house through a gender reveal type of event. Once classes start, children will be led to different corners and will open a big box with balloons or they will gather outside and a color will be assigned to them at the big reveal (details were still being worked out at press time).

Throughout the school year, students can receive a house point. Each time a point is received, the class does the house chant. “It’s a big deal to get a house point,” Stein says.

Additionally, there is a system for recognizing individual Greenwood students for “living their Gator Values.”

Other Schools Follow the Lead

The incorporation of the house system has been extremely positive, and other schools have taken notice. About fifty schools have visited Greenwood to learn about the system. In addition to a huge improvement in moral and a boost to the learning environment, SOL scores reflect the positive momentum: mid-90s on math and low-90s on reading. Greenwood, which has a diverse enrollment that reflects many ethnicities and a wide span of socioeconomic status, also boasts active parent and family engagement and PTA participation.

“Attendance has gone up, and the climate for students has improved,” Stein says. “Student and parent engagement has also gone up.”

Making an Authentic Connection

First-grade teacher Lyndsey Smith is inspired by Stein and his positive attitude. “He brought back my love of teaching. He can take a tiny idea and make it a huge success,” she says.

One of Smith’s favorite house-related activities takes place on Henrico County’s designated half-days. Prior to instituting the house system at the school, Stein says attendance was very low on those days. Now on half-days, each teacher at Greenwood can create a STEAM challenge for each house in their grade level. Houses rotate through the projects, and the day ends in a pep rally. “Kids say it’s their favorite day of the school year,” Smith says.

Inspired by Greenwood’s success, representatives from twenty other schools have visited to find out how to make the most out of half-days and to see the program.

Cara Jean O’Neal and her daughter, Ashton, who is a fourth grader at Greenwood this year, were excited when they heard about the house system. “I think it’s been a wonderful initiative for the school,” O’Neal says. “Ashton has had the chance to learn leadership skills that I wouldn’t think elementary students would have.”

Students are proud of being in their houses and also being Greenwood students, she adds. “It helps them tie into the values and practice them more than just seeing them posted on the wall.”

There is a new sense of belonging, the Henrico mom says. “It’s not only the kids, but the parents as well. The level of energy Stein brings has translated throughout the school and with parents.”

School has become fun, says Ashton, one of her school’s house leaders. “I like that you get to interact with other houses in a fun way. I enjoy school more now, and I’ve learned how to work better with other people.”

Making Authentic Education Connections

Ryan Stein’s tenure as principal of Greenwood Elementary School has been marked by the personal stories he often shares with students and staff members. One day, the school’s financial secretary, Jennifer Berdux, suggested he put those stories together and

Ryan Stein’s tenure as principal of Greenwood Elementary School has been marked by the personal stories he often shares with students and staff members. One day, the school’s financial secretary, Jennifer Berdux, suggested he put those stories together and

write a book. Stein liked that idea and so did Brandylane Publishers of Richmond. Lifeline 65: How Small Connections and Big Enthusiasm Can Change Education was released last month.

“I wrote it when I was on vacation,” he says. “Jennifer helped edit the book and bring the stories alive.”

In the book, available in Kindle and paperback on Amazon and at barnesandnoble.com, Stein shares best practices and innovative ways to build relationships with kids, as well as personal stories of educational inspiration, like the popular and successful house system. It’s full of small ideas that can lead to meaningful connections.

Inspiring, joyful, and heartfelt, the book is reflective of what education is all about, as well as what Stein has lived and faithfully practiced during his fifteen years as an award-winning educator. It was a top-seller on Amazon the first week of its release in July. “It’s about kids and relationships. That’s the biggest message,” Stein says.

He hopes teachers, principals, and schools can take “one idea from the book and implement it at school. That one idea might be the lifeline to a child and alter the course of where they might be going,” Stein says. “I hope [making authentic connections] can change one life of one child because it changed mine.”