The Future of STEM for Kids

By Joan Tupponce | Photos by Keith Cephus, NASA Langley, Kim Shiflett, Caroline Martin, David C. Bowman

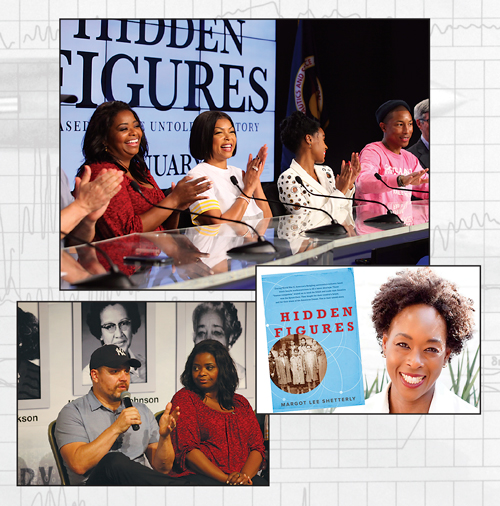

Like her colleagues at NASA Langley, Christine Darden never thought of herself as a pioneer. She was just doing her job. But now, after Margot Lee Shetterly’s New York Times bestseller, Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space Race, and the Oscar-nominated film that followed it, Darden, Katherine Johnson, Dorothy Vaughan, and Mary Jackson serve as role models for women and children everywhere.

Like her colleagues at NASA Langley, Christine Darden never thought of herself as a pioneer. She was just doing her job. But now, after Margot Lee Shetterly’s New York Times bestseller, Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space Race, and the Oscar-nominated film that followed it, Darden, Katherine Johnson, Dorothy Vaughan, and Mary Jackson serve as role models for women and children everywhere.

Early next month, Darden and Shetterly will serve as grand marshals of the Dominion Energy Christmas Parade in Richmond – traveling down Broad Street in grand style waving to thousands of families along the traditional parade route.

Both Shetterly’s book and the award-winning film are based on actual facts that reveal the struggles black women faced regarding race and gender equality while working at NASA Langley Research Center in Hampton from the 1940s through the 1960s.

All four of the women in the book worked in what was called the “human computer” pool at Langley doing complex computations and equations for engineers. “There weren’t very many women in management jobs at Langley, except maybe human resources and administration,” says Darden, who remembers reporting to a white female supervisor when she started at the research center in the late 1960s.

The Road to Langley

Growing up in the small town of Monroe, North Carolina, Darden was always interested in the intricate details of how things worked and why. “I was taking bicycles apart and helping Dad with the car,” she recalls. “When I was outside, I was playing – usually with the boys.” In high school, something just clicked for her when she took geometry, and she fell in love with math. She was headed to Hampton Institute to major in math when her father suggested she major in math education instead, so she “could be assured of getting a job,” she says, noting that she minored in physics education as well. “I took as much math that wasn’t required [for my degree] as I took electives.”

She taught math in Brunswick County for a year after graduating from Hampton in 1962, and then moved to Portsmouth where she taught for another year. She left teaching when she got the opportunity to serve as a research assistant in the physics department at Virginia State College (now Virginia State University) working on aerosol physics. “By that time, I realized I liked the application of mathematics,” she says. “I went on to get a master’s in applied mathematics, and then was hired by NASA in 1967 as a data analyst.”

She worked in the “human computer” section of the reentry physics branch of engineering where they calculated the altitude, angle, and temperature for spacecrafts reentering the earth’s atmosphere. “The heat generated can be thousands of degrees,” she says of reentry. “They had already done the calculations for Apollo before I got there.”

After working in the human computer section for five years, she realized the engineers using her calculations were trying to solve the same type of problems she had worked on in graduate school. “That’s what I wanted to do,” she says of going into engineering. “I started asking about being transferred, but I was turned down at first. So I asked at a higher level, and I was transferred.”

She was one of only a few female aerospace engineers at NASA Langley at the time.

Her first assignment was to write a computer program for sonic boom minimization, a field of research that she stayed in for twenty-five years. She went on to receive her doctorate in mechanical engineering from George Washington University in 1983 and became the technical leader of a NASA program in which she developed sonic boom research. In 1999, she was appointed as the director in the program management office of the Aerospace Performing Center where she was responsible for Langley research in air traffic management and other aeronautics programs managed at other NASA Centers. She was the only black female from the human computer department in NASA Langley’s history to become part of its senior executive service.

The mother of three daughters (and now, five grandchildren and three great-grandchildren), Darden admits it was difficult sometimes to juggle all of her responsibilities at work and at home. “There were times on the weekends when I would have to study because I was taking classes,” she says. “Sometimes I would have to stay a little longer on my shift at work to get things done.”

Retired and living in Hampton, she is excited about the fact that NASA is moving forward on building a supersonic low boom experimental airplane in the next five years that would continue her work on sonic boom testing. Currently airplanes are not allowed to fly supersonically over the United States.

“The Concord didn’t have a lot of routes it could fly across land,” she says. “If we can get the FAA rules changed and get an airplane that doesn’t disturb people, we will have routes everywhere that people could fly. It will make travel around the globe faster. I am pretty excited to see that airplane built and the FAA rules changed, so we will have regular supersonic flights.”

While she still doesn’t see herself as a pioneer, she understands it means a lot for students, especially women, to see someone doing a job they want to do. “They realize that it is possible for them,” she says.

She now speaks to students of all ages, from elementary school to college, about her work and the importance of STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math). “Students come up and talk about how inspired they are and how they like math and science,” she says. “They have to keep taking the classes and do the work. Apparently, that is what the movie Hidden Figures has inspired in a lot of people.”

While the film dramatizes some of the real-life events and doesn’t always depict events in the right time sequence, Darden says the “hard points of the film were accurate.” She admits she didn’t think about lessons associated with the movie until people started asking her to point them out. “They didn’t quit,” she says of her counterparts at Langley. “They did their work and did it well. They prepared, and they spoke up for what they wanted.”

Darden was honored when the parade planners in Richmond asked her to serve as a grand marshal of the Dominion Energy Christmas Parade. “I’m looking forward to it,” she says. “It should be a great experience.”

From Hidden Figures to Modern Figures

Julie Williams-Byrd, deputy chief technologist at NASA Langley Research Center, has been working at the organization for twenty-nine years and was at Langley when Darden worked there. Williams-Byrd was selected as an ambassador in the Modern Figures program when NASA reached out to Langley seeking scientists to represent the agency and inspire future generations to explore STEM fields.

“When the book came out, NASA saw the opportunity to allow those engineers who are female – and especially African Americans and others who are in under-represented communities – to be a showcase and let young girls see that we are here at NASA,” she explains. “We talk to young folks so they can see what opportunities there are. We talk about the things that helped us get to where we are.”

A native of West Haven, Connecticut, Williams-Byrd graduated from Hampton University where she earned both a bachelor’s and master’s degree in physics. When she started high school, she says she wanted to be a Supreme Court judge because she was excited by the work of Thurgood Marshall. But her father suggested another career based on her talents.

“When I was a senior in high school, my dad had been reading engineering magazines and said ‘Why don’t you think about being an engineer? You are good in math, and I think you can do this,’” she says.

That inspired her to take a class in physics. “My instructor made physics open up to me. I could see it and excel,” she says.

Now she wants to give back by helping young girls see their potential. “Other people see the potential in you and help and encourage you,” she says. “That is why I am so passionate about helping others.”

She realizes it’s not always easy to choose a different path. When she first started at Langley, it was very intimidating for her. “First of all, you are female, second, you’re African American, and third, you graduated from a historically black college,” she says. “But you have to tuck that in, and realize what you do – and do that.”

Even as gifted as Katherine Johnson was at an early age (the main character in Hidden Figures), “she had a time when she doubted what she did,” Williams-Byrd says. “But she knew what she could do and she persevered. You have to work hard and people will see what you do. ”

This year, as NASA Langley Research Center turns one hundred, Michelle Ferebee, mathematician and computer scientist at NASA Langley (and a designated Modern Figure), is serving as chair of the centennial celebration. She began working at Langley after graduating from William & Mary. “I was one of the first black females to graduate from William & Mary’s math department in 1983,” she says, adding that Mary Jackson and Katherine Johnson were still at Langley when she started working there.

Ferebee has been interested in math her entire life. “I tell people ‘somebody forgot to tell me that girls couldn’t be good in math.’ I always assumed I could do it, and I always enjoyed it,” she says.

She is pleased Hidden Figures has brought awareness to NASA Langley so people can understand all of its contributions. “Many people equate NASA to Florida and Texas. There are some people in Virginia who are not aware it exists,” Ferebee says of the center. “With this centennial celebration, we want to get the word out that we are here, and let people know about the great work we have done in the last hundred years.”

It’s important for the center to inspire the next generation. “We definitely want to inspire both girls and people from under-represented groups to go into STEM fields,” Ferebee says. “We have robust intern programs here. We also go out into classrooms.”

Local Efforts: Looking Toward the Future

Having role models – like the real women depicted in Hidden Figures – is a good start, and getting girls interested in math and science at an early age is equally important to increasing the number of girls going into STEM fields.

“What we see is that middle school tends to be a big turning point. Kids are looking for their gender roles at that age,” says Lorraine Parker, director of diversity and student programs in the School of Engineering at VCU. “You have to get them thinking that they want to and can do STEM.”

The number of women across the nation applying to schools for engineering and computer science is low with the exception of bio-medical engineering, which often leads to medical school. Parker roughly estimates that women represent only 20 to 25 percent of current VCU students in the field of engineering, but that number is growing.

“When you talk to high school-age females, they aren’t interested in science, engineering, and computer sciences because they want to do something that helps people,” Parker says. “They have the perception that working in engineering and computer science won’t help people or society. We lose girls because of that.”

But that’s not the reality. Engineers and computer scientists are involved in areas such as pharmaceutical engineering, surgical equipment development, and software creation for a variety of uses, including helping the visually impaired.

“We have to reeducate society as a whole – the purpose of engineering is to develop products that will help people and improve society,” Parker says.

She believes more women will get into engineering and computer sciences. “We have companies coming for job fairs that want to interview women and minorities. The change won’t be overnight, but it is changing.”

CodeRVA Regional High School, the new public school serving students from thirteen area school divisions, should help facilitate change. When he was reviewing applications for students, Executive Director Michael Bolling found that the number of young women applying to the technology-focused public high school was low.

“We realize that the technology field needs more females,” Bolling says, adding that current enrollment is split equally between males and females, yet far fewer girls than boys applied for admission to CodeRVA.

The school, which opened in September, received 756 applicants and currently has ninety-three students. Bolling wants the school to be reflective of the Richmond region in regard to race, gender, and socio-economics. “In talking with technology employers in the region, they said they were lacking in diversity in terms of gender (female) and race in general,” he says. “That was one thing we heard loud and clear.”

Bolling hopes CodeRVA will help create a paradigm shift for the technology industry that opens doors to opportunities for women. “We want to help build that pipeline,” he says.

Running from the “human computer” pool at NASA Langley, to NASA’s Modern Figures, to VCU, to CodeRVA – it’s a pipeline that serves to benefit us all.

Don’t Miss the Dominion Energy Christmas Parade

The thirty-fourth annual Dominion Energy Christmas Parade takes place on Saturday, December 2, 2017, at ten o’clock. Dr. Christine Darden, mathematician and aeronautical engineer from NASA Langley, and Margot Lee Shetterly, author of Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space Race, will serve as co-grand marshals.

“I love the fact that Christine Darden is one of the women from the story Hidden Figures who has made a real impact on the aeronautical industry,” says Tera Barry, communications vice chair of the Dominion Energy Christmas Parade. “Children will be able to see a real life hero being celebrated, and our hope is that they will see that this could be a future for them, too.”

The parade kicks off at the Science Museum of Virginia and continues east along Broad Street to Seventh Street. Each year, it attracts more than 100,000 spectators from all around Virginia, with thousands more enjoying the television broadcast on CBS6.

As always, the parade will feature marching bands from local high schools and colleges, dance troupes, giant helium balloons, floats, Legendary Santa himself, and the also legendary Harlem Globetrotters.