By Joan Tupponce

“What he saw was devastating,” Worthington says. “The house was a wreck, and there was blood everywhere in the hallway. That’s when he saw our mother’s body on the floor.”

A seasoned psychologist at Virginia Commonwealth University, Worthington packed and repacked his bag five times in preparation for the trip to Knoxville, Tenn. His wife, Kirby, remembers: “When we got the call about Mom, we were all stunned and in disbelief. Ev’s way of handling bad news is to do something.”

A few hours later, Worthington was standing in his childhood home, viewing what he describes as “a horrific sight.”

His 76-year-old mother, Frances McNeill Worthington, had been beaten and sexually abused before being killed with a crowbar. “I was so angry,” Worthington recalls. “I sat in the back room and pointed to a baseball bat. I told my brother and sister that I would beat the man’s brains out.”

That night, Worthington was consumed with rage and insomnia, replaying the scene in his mother’s house over and over. It took a while for him to remember what had kept him up nights just a month earlier — a publisher’s deadline for his book, To Forgive Is Human. As a marriage counselor since 1982, he had examined the concept of forgiveness for several years. Now, under the most brutal of circumstances, it was time to apply it to his own life.

“It dawned on me that I had come through that whole day never allowing myself to think the word ‘forgive,’ ” he says. “I had just written this book on forgiveness, and I wasn’t going to think about forgiveness. Who did I write the book for? Everybody else?”

A Way Out

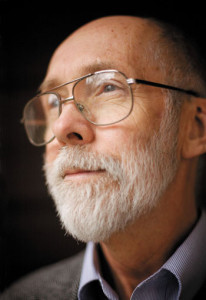

The memories of that night in 1996 are as vivid today as they were then for Worthington, who leans back in his VCU office, crammed with books, files, family photos and mementos. At 62, the seasoned professor is lanky, with a stubby white beard and a wide smile that he flashes often.

The oldest of three children, he grew up in a two-bedroom house with a coal-burning stove in the hallway, after his parents moved to Knoxville from coal towns in East Tennessee. His father was a brakeman for the railroad and spent three out of four days out of town. When he was home, he drank.

“That made relationships with him strained,” Worthington says. “As a psychologist, I now can recognize that mom was unipolar depressed. She was hospitalized three times.”

Despite the unevenness of their home life, Worthington’s parents underscored one lesson: Education is the way out of poverty. “Because of that, all three of us kids ended up getting advanced degrees,” he says — nothing short of a miracle coming out of Knoxville South High, then one of the academically weakest high schools in town. “They didn’t send many people to college.”

Worthington was accepted at the University of Tennessee, paying his tuition with the money he had saved delivering newspapers during high school. His educational goals were lofty — he wanted to get his master’s in engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and an MBA from Harvard. He applied for and won a national fellowship from the Atomic Energy Commission, which gave him a full ride to the school of his choice. At MIT, he earned his master’s degree in nuclear engineering in 1970, and Harvard Business School was beckoning with a fellowship.

But with the Vietnam War draft at its height, Worthington decided to attend the Navy’s Officer Candidate School to avoid the front lines. He was sent to Mare Island Naval Shipyard in San Francisco, where he taught nuclear-reactor physics.

“It was either do that or be stationed on a destroyer,” he says with a sly grin. “Wisdom said I could defend San Francisco better than the Gulf of Tonkin.”

The same year he received his commission, Worthington married Kirby, whom he predicted he’d wed back at UT, when they met through student government.

Kirby, tall and slender with graying, shoulder-length hair, is still charmed by her husband’s humor and unpredictable nature, both of which have endured through the years. One day after they were married, he called her and tried — in vain — to disguise his voice with a nasal twang, telling Kirby he had kidnapped her husband, and she could locate him only by following directions on a tape in their mailbox. Kirby followed the directions and made her way to Deep Run Park, where she found her husband loosely taped to a tree, a blanket and picnic basket on the ground nearby.

“He took the time not to let life be routine,” Kirby says.

At Mare Island, Worthington discovered that he had a passion for teaching and also counseling, a career path he had never anticipated. “It was stressful for everyone,” he says. “The penalty for failure was huge. If they didn’t pass, they were busted down and activated.”

Several of the students had difficulty handling the stress, but most officers weren’t willing to help them deal with their emotional problems. Worthington was the exception. “I enjoyed working with them,” he says. “I did a lot of informal counseling. That’s what convinced me that I wanted to make a career shift.”

After serving his stint in the military, Worthington attended the University of Missouri at Columbia, where he received a Ph.D. in psychology and counseling. He accepted a teaching position at VCU in 1978.

He remained there to direct a psychology clinic and also had a private practice in marriage counseling. It was then that he recognized the value of forgiveness. At the time, Worthington was working with a couple that was having trouble salvaging their marriage. “I was sitting in my office thinking, ‘What is wrong with these people? Why aren’t they getting better?'”

That line of questioning led him to design an intervention that would help people forgive each other.

The steps in Worthington’s plan require effort and patience. They ask that you recall the hurt and be sympathetic to the other person — to empathize with the person who hurt you. “You need to allow yourself to give the altruistic gift of forgiveness and commit to the forgiveness you have experienced,” Worthington says. Lastly, you must hold onto the forgiveness when you are in doubt. Being unable to forgive and ruminating about negative events is often linked to depression, obsessive/compulsive behavior and other disorders.

“It’s good for you to give it up,” Worthington says. “But it’s not an easy sell.”

Life’s Worth

Worthington’s own struggle continued after his mother’s death, when the case against the teen accused of her killing fell apart. Four days after the murder, the boy was singled out as a suspect because he had been involved in some burglaries in the area. When he was being questioned, he admitted to the crime but never made a formal statement, and because his lawyer was not present at the time, the confession was dismissed. In addition, the two pieces of evidence found in the case became inadmissible because they had been contaminated through improper handling.

The teen later admitted to burglarizing the house but said he didn’t commit the murder. The case went to the grand jury, which refused to indict him because there was no physical evidence. The murder is now a cold case.

Worthington’s brother, Mike, never got over the tragedy, and he committed suicide in 2005, at the age of 54. Worthington was in Europe when he received the news.

“Ev really struggled with trying to forgive himself for not being there for his brother,” Kirby says. “He tried to use his forgiveness model on himself, but forgiving yourself is hard. In some ways, Ev may still be dealing with that.”

There are still moments that trigger thoughts of his brother’s suicide, but Worthington doesn’t let it dominate his life.

Though his days are consumed with teaching, writing and public speaking, he always steals time for himself and his family. When his children were small, the family would often go camping and hiking, and exercise continues to be part of Worthington’s daily life.

He strives to walk 1,200 miles each year. He’s also an avid tennis player, ranked third in the state for men age 60 and older, and 10th for men age 55 and older in the Mid-Atlantic section of the Unites States Tennis Association. “Everett is always a gentleman on the tennis court,” observes Steve Rowe, a frequent tennis partner. “He gets frustrated when he’s not at his best. He’s a true competitor but gracious in defeat and victory.”

Worthington is just as competitive on the dance floor, having started dancing when he took ballroom as an elective at the University of Tennessee. Years later, he and Kirby joined the USA Dance Club in Richmond. “We even took the kids for a Saturday workshop, and they were hooked,” Worthington says. “After that, it was a family thing.”

In 2005, when Worthington traveled to England for a scholarly leave at the University of Cambridge, he and Kirby took time out for ballroom lessons. “They taught us the very stylized international ballroom dances,” he says. “At the time all we knew was American, which is more free-flowing.”

Two years ago, he danced in front of thousands at the Richmond Coliseum during a local dance-off as part a tour affiliated with television’s Dancing With the Stars. Twenty-five couples tried out before the field was narrowed down to 10. Worthington and his partner ended up losing to a young couple. “It was great fun, but I probably wouldn’t do that again,” he says. “I had my shot at the brass ring.”

Walking the Talk

By 1988, Worthington’s five-step forgiveness plan — known as REACH — was being used by other professionals in the field. Two years later, the Journal of Psychotherapy published his first professional article on the subject of forgiveness.

Today, Worthington is one of the world’s leading authorities on forgiveness. He’s authored 22 books on marriage, family and forgiveness and has spoken around the world. He’s made more than 250 appearances in different media as an expert in the field, including Good Morning America and CNN.

Over the years, Worthington has won over skeptics, including Mary Ann Ryan, his assistant when he was chair of VCU’s psychology department.

Ryan admits she was at first hesitant about accepting Worthington’s forgiveness model. “I couldn’t understand how anybody could be that forgiving, until I read his writings on [the subject],” she says. “When you get into the work he’s done, you can understand the value of forgiveness.”

Dr. Steven Danish, director of the Life Skills Center at VCU, classifies Worthington as not only “one of the best known researchers in forgiveness” but also a man with an exuberance for life. “He has a lot of different areas of interest, and he uses life experiences to the fullest. That is not that common in people doing research. Faculty members like to think of things as they develop ideas from theory. I think you develop ideas from experience and then look at theory. He’s done that well.”

Worthington’s work led him to the John Templeton Foundation, which supports research and scholarship on core themes such as forgiveness. In 1998, he served as executive director of the foundation’s Campaign for Forgiveness Research, which raises funds for scientific research. Campaign chairs included Archbishop Desmond Tutu, and President Jimmy Carter was also a supporter of the campaign.

“Dr. Worthington was central to overseeing research and scientific studies to explore the unique role of forgiveness in healing individuals, families, communities and nations,” says Pamela Thompson, Templeton’s vice president of communications. “He also has personally made great strides in his own forgiveness. He’s a humble, dear, dear man.”

Worthington’s concept is reinforced in a recent 63-minute documentary film by Paulist Productions, The Big Question. The film on forgiveness, now being shopped to television markets for national and international distribution, was screened at VCU this past summer. Worthington is the subject of one of five vignettes — Frank Desiderio, Paulist’s president, was drawn to his story because of its dramatic elements.

“The film has an emotional effect on people,” he says. “Everett’s story had a strong emotional pull. He speaks about forgiveness not just from a scientific point of view but also a personal point of view. He became a key figure in the film because he had walked the talk.”

Although his family tragedies remain present in his mind, Worthington has been able to achieve a measure of peace. He remembers the exact moment when he forgave his mother’s killer.

“I saw myself looking at the baseball bat. I thought to myself, ‘Whose heart is darker — mine or his?’ ” he says. “That was the moment when I forgave him. It changed my whole life.”

One of Worthington’s major tenets is to never insist that people forgive. It’s a personal decision. “Many people say it’s good to do, but it’s impossible — that it’s an ideal for great religious leaders but nobody else,” he says. Still, he believes that people can find peace from forgiving. “You get the peace by replacing negative emotions with more positive emotions to the person who hurt you. It requires days of effort to try to see things from the point of view of the person who hurt you.”

Forgiveness doesn’t shorten your grief or mean that you don’t want justice, but it will “change the product you come out with at the end of your grief.” Worthington says he has never wavered on forgiving his mother’s killer. “It’s what Mamma taught us. It would be dishonoring to her for us to go against her teaching.”